Those who are familiar with “Route 66: The Mother Road” author and speaker Michael Wallis know that he cites the allure of Route 66 pretty regularly.

However, in the past week or so, he has given the ol’ Mother Road considerable publicity by even his standards.

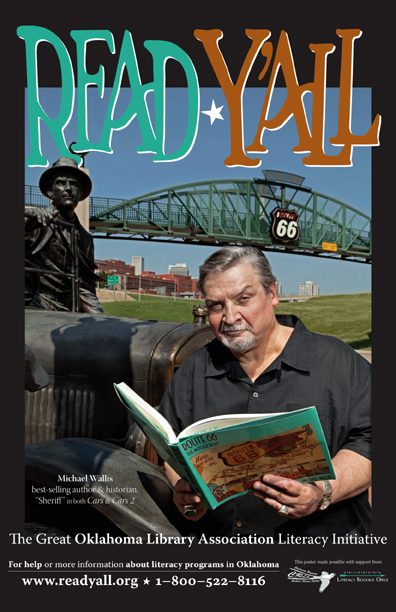

First, this poster will go up in libraries across Oklahoma as part of the Oklahoma Library Association’s literacy initiative. Yes, that’s his best-selling book in his hands and the Cyrus Avery Centennial Plaza in Tulsa in the background.

Second, Wallis gave a memorable keynote speech at the inauguration ceremony for Tulsa city officials. Apparently no one saw fit to record or videotape it, but we do have a transcript. You can read it in its entirety after the jump:

I discovered Tulsa in the course of a trek through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma in June of 1980. I encountered familiar places and saw old friends as I passed through country I knew well. But I took my time when I got to Oklahoma, sticking to the back roads, driving past wheat fields and ranch lands and along rivers and lakes.

I went up and down Oklahoma’s favorite highway and America’s Main Street—Route 66. I met blue bloods, rednecks, busted-up cowboys, beauty queens, and American Indian elders whose quiet eloquence spoke volumes. I saw towering art deco palaces and beautiful tallgrass prairie.

As I would later write, I came to Oklahoma expecting to find bland hamburger. Instead, I discovered a rich chili made of filet mignon and loaded with spice.

It was a good trip. One of my best. And the highlight of the entire journey was my time in Tulsa. I slept in the Mayo Hotel, toured the Gilcrease Museum, filled with treasures by Remington, Russell, Moran, and other world-class artists; the Philbrook Museum of Art with its manicured gardens; and I took in the down- home charm of Cain’s Ballroom, where Bob Wills invented western swing.

That was just for openers. I also devoured barbecue so succulent that I purred like a cat, listened to jazz and blues that was out of this world, and viewed the largest collection of ceremonial and aesthetic Judaica in the Southwest.

Within two years my wife, Suzanne, and I packed up and moved to this place between the edge of the Great Plains and the foot of the Ozarks on the Arkansas River in northeastern Oklahoma. We became part of this land of lakes and rolling hills where Tulsa serves as an oasis of culture and commerce.

We soon found that Tulsa is a city that has paid its dues and then some. The result is a place that combines the hospitality of the South, the charm of the Southwest, sophistication of the East, and solid Midwestern values.

Yet too often, Tulsa, like the rest of the state, falls victim to something of an identity crisis. Visitors driving the shaded residential streets that crisscross Tulsa’s orderly neighborhoods often comment that it feels as if they are in Connecticut or a city in the upper Midwest. So where does this city fit in the scheme of things?

To tell people about the city I now call home, I like to start with its heritage, which traces back to 1836. That was when a band of Creek Indians, uprooted by the federal government from their ancestral homeland in Alabama, trudged up a low rise overlooking the east bank of the Arkansas River.

Mercifully, their journey of sorrow finally came to an end in Indian Territory. Beneath the boughs of a sturdy post oak, the Creeks deposited the ashes and embers they had carried from their last campfire on their native soil. As darkness fell, they kindled a new council fire. They paid tribute to the land they left behind and the many family members who perished during the two-year journey. At that instant, with long shadows dancing in the glow of fresh flames sparked from the coals, the settlement was born that eventually came to be known as Tulsa. The Creeks had brought a sense of place with them and now this land truly was their new home.

“It was a strange beginning for a modern city—the flickering fire, the silent valley, the dark intent faces, and the wild cadence of ritual,” wrote historian Angie Debo many years later.

By the late 1800s, the Creek settlement grew into Tulsey Town, a cow town with dirt streets and false-front buildings. But shortly after the turn of the century, that all changed when oil was discovered at nearby Red Fork and Glenn Pool, one of the largest oil fields of its time. The boom was on.

Oil made Tulsa. Promoters championed Tulsa as the proper headquarters for oil captains to conduct financial business and establish their offices and homes. The lure of “black gold” swelled the city’s population as the influx of new Tulsans built schools, hotels, and even an opera house. By 1912, the city was becoming known as the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Recently, when fellow author Bill Bryson came to town and discussed his latest book about the nation in the year 1927, I was asked to also speak and expound on the state of the city of Tulsa in 1927 — that pivotal year when the nation was between wars and on the wagon and Tulsa was dead sure of its future.

We spoke in one of my favorite Tulsa venues — that Valhalla of Western Swing that came to be Cain’s Ballroom, but in 1927 was still a garage housing the fleet of cars owned by the late Tate Brady. KVVO Radio — the voice of Oklahoma —moved from the Route 66 town of Bristow that September of ‘27 and set up shop in Tulsa. Within a few years, Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys would be broadcasting live on KVOO from the stage at Cains.

Tulsa was hot stuff in 1927. There was plenty of opportunity and plenty of sass.

This was a city that believed its own publicity. It was a place tailor-made for risk takers and they were here in great numbers — rough and tumble oil tycoons, with sixth grade educations and nouveau riche ambitions. They swigged the best bootleg whiskey neat, literally and figuratively rolled the dice and cut the cards, and blew clouds of cigar smoke in the face of Lady Luck.

The city was the Oil Capital of the World by God! It had become so connected to petroleum that in 1927, deep in the heart of Texas, a new oil patch settlement was named Tulsa, after the big Oklahoma boomtown. By 1927, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was headquarters of 1,500 oil-based companies. Black gold flowed like the lugs of 90-proof booze that bootleggers dropped off at masonic lodges, oil tycoon’s homes, and politician’s offices. It was a time for a host of rascals with a streak of larceny in their hearts smelling of bay rum and pomade and clad in Kansas City suits and glossy wing tip shoes.

The excitement of oil discoveries in the region quickly gave birth to great community pride and spirit. Highly productive oil fields lubricated and drove the city as bold risk-takers and daring entrepreneurs from across the nation flocked to the area and left their marks.

Working stiffs with enough moxie could make a buck. If you lived on the west side of the Arkansas in 1927 and could take a punch and then deliver a knockout, if you could roll up your sleeves and weren’t allergic to hard work, and if you didn’t mind being bathed in sweat and raw crude oil, then you were definitely in the right place and at the right time. Of course, it goes without saying, it also helped if you were someone with white skin.

The wounds of the appalling massacre of untold numbers of black citizens just six years before were far from being healed. That process would take many years and still remains a work in progress. But the ashes and blood of Greenwood were stirred into a mortar of resiliency that bound people together and kept hope alive. Even that horrific episode of our history, stirred by elements of the Ku Klux Klan, could not smother the aspirations of the majority of Tulsans, regardless of race or religion.

The summer of 1927 was hot but not nearly as hot as the music scene in Greenwood where sweet jazz reigned. That summer a twenty-three-year-old piano player from New Jersey, was in town with a touring vaudeville act playing at the Dreamland Theatre on Greenwood Avenue. He was awakened in his bed at the Red Wing Hotel by the Blue Devils, a jazz band performing on the back of a flatbed truck. He had never heard anything like it. That night changed his life and he later said it was the single most important point in his musical career. That young musician became known around the globe as Count Basie.

Meanwhile that summer over at McNulty Ball Park — that in 1921 became a holding pen for terrified black families displaced by white rioters burning their homes — baseball fans were screaming themselves hoarse. Their beloved Tulsa Oilers led by Boom Boom Beck, Stew Bolen, Red Kress, Rollie Naylor, and Guy Sturdy finished in first place in the Western League. But in ’27 nobody in the bleachers knew that in just two years the ballpark — where babe Ruth played exhibition games and Jack Demsey boxed — would be demolished to make way for the art deco Warehouse Market.

The building boom was well underway in Tulsa in 1927. That year, construction costs in downtown Tulsa alone were averaging one million dollars a month and within three years the city had more buildings of ten stories or more than any other city of its size in the world. Waite Phillips, the quietly aggressive oil man and brother of Frank up in Bartlesville, was responsible for many new buildings such as the ornate Philtower, erected in 1927 and dubbed “The Queen of the Tulsa Skyline.”

Yet by far, the grandest personal achievement for Waite Phillips in 1927, was the completion of his palatial family home — the Villa Philbrook, which Edna Ferber pronounced “wasn’t a house at all, but a combination of the palace of Versailles and the Grand Central Station.” The 1927 party Waite and his wife Genevieve hosted for 500 of the rich and famous of Tulsa and far beyond was said to have been the most memorable in the city’s social history.

Until the Phillips family was able to make the move into the sprawling Villas, their home in 1927 was a brick residence on South Owasso in a prime neighborhood. Just two doors away from the Phillips house, was the home of Cyrus Stevens Avery and his family. Avery, a businessman and civic leader, was largely responsible for the campaign that created Route 66, the brand new highway linking Chicago to California that came right through Tulsa. In 1927 Avery established the U.S. Highway 66 Association and he soon became known far and wide as the “Father of Route 66.”

Both Cy Avery and Waite Phillips attended the banquet held the evening of September 30, 1927, at the Mayo Hotel to honor Charles Lindbergh, who just a few months before had made his historic solo flight from New York to Paris. Earlier that day, “Lucky Lindy” —on an aeronautics promotional tour sponsored by Daniel Guggenheim — landed the Spirit of St. Louis at McIntyre Field. During the dinner at the Mayo, the guest of honor, politely chided the city leaders present for allowing a place as grand as Tulsa to not have a proper airport. Phillips, Avery, Bill Skelly and other captains of industry heard Lindbergh loud and clear and by the following year the Tulsa Municipal Airport was open and soon became one of the busiest in the nation.

Then as is the case right now, for the most part, Tulsans were filled with a sense of purpose. Every day those of us who live in Tulsa bear witness to what those before us accomplished for our city. All sorts of folks built Tulsa. They were people from all walks of life. Some of them lost big. But all of them, winners and losers, left us so much by risking big money on big notions.

The true legacy of those dream merchants is much more than bricks and mortar. This city is still young and precocious. I’d sum up Tulsa’s history in a single word: energy. Not the kinetic stuff that results from oil and gas and the refined products reaped from the earth, but another sort—the human variety. It’s what powered the flamboyant fraternity of early oil discoverers and wildcatters. It’s the same thing that stirred the determined Creeks, Tulsa’s first citizens, and inspired cattlemen, railroaders, roustabouts, and all the rest who used muscle and mind to make this city grow.

When the oil industry declined, farsighted Tulsans helped us get through the recession and oil bust that started in 1982, when gas prices went into a free fall and many oil firms pulled out of Tulsa. Instead of turning tail or wringing their hands, Tulsans worked hard to diversify the city’s economy by attracting more aviation, telecommunications, health care, and technology businesses to the city.

Still, we needed a plan. As one pundit put it: “It is time to pitch in a penny or turn out the lights, and Tulsans are not the fleeing kind.” True to form, the citizenry did not flinch. In 2003, following lengthy debate and public hearings, Tulsa County voters overwhelmingly approved a one-penny, 13-year increase in the sales tax for four initiatives that covered a wide range of economic development and capital improvements for the region.

This package—called Vision 2025— stimulated new jobs and opportunities, created educational programs, and encouraged private investment in Tulsa’s downtown. Foundations and the private sector stepped up and offered millions in matching funds. Several municipalities began construction of community centers, recreational facilities, and other infrastructure projects. Funds were also earmarked for construction of health care, research, and higher educational facilities, the Tulsa Air and Space Museum, Oklahoma Aquarium, Oklahoma Jazz Hall of Fame, American Indian Cultural Center, neighborhood and park beautification, and the preservation of the historic Route 66 corridor, an effort that continues to this day with even more great things to come where “East Meets West” at the historic Cyrus Avery Plaza on the Arkansas.

In downtown Tulsa, the 18,000-seat BOK Center has been described as “the crown jewel” of the Vision 2025 program drawing tens of thousands of people for cultural and sporting events. All around it, investors are still buying up any available property in downtown Tulsa and recycling historic buildings for business and residential use. Locals and visitors frequent the restaurants, galleries, and shops in the Brady, Blue Dome, Cherry Street, Sixth Street, and Brookside districts.

Tulsa often has been fortunate to find strong leaders. Today, as the men and women we have picked to represent us are sworn into office for a fresh term of service, the hope is that they will keep a keen eye on their role models from the past. We trust that all of them truly understand the importance of tapping human energy in order to guide Tulsa into the future.

That is why I remain optimistic about my adopted city and its citizens, and why I have no regrets about moving here so many years ago. For me there is no better place to be right now than Tulsa, where every day I see the results of the significant economic development and investment surge that fuels and invigorates the city. Risk takers—thought to be an endangered species—are making a comeback.

Our energy level is high and our watches are set on Tulsa time.

And that time is now.

(Speech transcript via city councilor G.T. Bynum)

I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Wallis at three Route 66 Festival. He graciously signed my copy of thE Mother Road. Our brief visit was one of the highlights of the festival.